A Struggle To Be Open-Minded

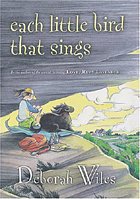

Deborah Wiles won me over with her book Each Little Bird That Sings, but it was a close call. Wiles' book is serious Southern eccentric, and I find Southern eccentric a stereotype that I grew tired of a long time ago.

I realize my response to this kind of thing may be due to the fact that I am a cold-hearted New Englander. Or the south may just be too far away from my reality for me to accept.

True, I do have a cousin named Junior, one of my aunts was once married to a man named Stubb, and I'm told I used to have a Great-uncle Boy. But as a general rule, we in the frozen north don't saddle our off-spring with names like Edisto and Florentine, Comfort, Tidings, and Declaration. (Comfort and Tidings are siblings in Each Little Bird, off-spring of Joy.) We prefer names like "Blackie" and "Brownie" for our dogs to names like "Dismay." The New England child has not been born who would describe a closet as smelling "like opportunity" the way Comfort does in Each Little Bird. And though we love our mothers, we don't go rattling on and on about it, even in our own thoughts. Though I've heard that grown men call their mothers "Mama" in the south, here in New England, no mother would allow her child to use the word past the age of, say, eighteen months.

I know that southern novels are written by southern writers, and I assume they know whereof they speak. I just can't take it. So, really, there was a lot to annoy me in Each Little Bird That Sings.

What I liked, though, was the main character, Comfort's, despair, not over the deaths of her elderly relatives, but over the erosion of her friendship with Declaration. Comfort's family had been running a funeral home for generations, and she could accept death and she could accept that you have to grieve over the lost of a loved one. Betrayal and rejection are another thing. Though I may be reading a little into the book, it seemed to me that Declaration was moving away from Comfort toward other girls (stereotypical "mean" girls, to be honest) because she just couldn't accept who Comfort was any longer. She couldn't accept that Comfort was part of a family business that worked with the dead and grieving. To be rejected because of who you are...man, that's rough.

I also liked Comfort's poor cousin, Peach. (There's another one of those names.) Peach is a heart-breaking character, one of those misfit children who really do show up in real life, even here in New England. In appearance, behavior, and temperament, they just can't fit in. Other children and sometimes even adults are put off by them. I've known kids like Peach. Everyone has known kids like Peach.

I very much appreciate that Comfort was filled with anger and bitterness, and she didn't just roll over and forgive. I appreciate that Wiles goes for a realistic ending instead of an easy, heart-warming happy one--which she could have done.

I think this book probably gets a lot of attention because it deals with death. And it does that well. But for me what raised this book up over my personal objections to it was not the lesson on death but the portrayal of the children's struggles with living.

No comments:

Post a Comment