We’ve got a first for you here at Original Content—a conversation with another writer, Susanna Reich, author of Painting the Wild Frontier: The Art and Adventures of George Catlin, which was published in August by Clarion Books.

Fiction vs. Nonfiction

GG: I was taken with Painting the Wild Frontier because I could see so many parallels between George Catlin’s life and that of Ethan Allen, whom I researched and wrote about. Both men didn’t begin the work they’d become known for until after they were thirty--Catlin, painting Indians in the western frontier; Allen, organizing what some might describe as a guerilla militia of poor farmers in what was then the frontier of the Green Mountains. Both men tried their hands at business—Catlin ran his own elaborate exhibits of his art; Allen was a land speculator. Both men were what might be described as flawed—Catlin seemed to be hunting for that big financial break that never came; Allen was a heavy drinker (even by the standards of his time) and, in my opinion anyway, a bit of an overcompensating blowhard. Yet both men became voices for people who otherwise wouldn’t have had one. Both these guys could easily have been characters in novels, and their real life stories could have served as their storylines.

Though you have written historical fiction, Susanna, you chose to write an historical account of George Catlin’s rollercoaster life. Why did you decide to go that way?

SR: Yes, Catlin’s life could have been a novel. But why create a fictional story when the real one is so exciting? It’s my job as the writer to find a subject whose life story is inherently dramatic, to research it thoroughly, and then to tell that story so that it’s vivid and suspenseful, as well as factual. I prefer not to make up dialogue or put thoughts in my subject’s head, and try to keep conjecture to a minimum. Facts aren’t dry if they’re well presented.

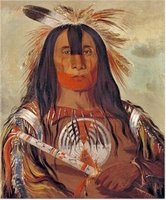

Also, remember that illustrations play a really important role in nonfiction. That’s especially true here, because Painting the Wild Frontier is about an artist. The illustrations provide crucial visual information. There’s additional information in the captions, too—they function like mini-sidebars. Between text, pictures, and captions, the reader gets a kind of multi-layered experience that’s not possible with fiction.

GG: I think you’re right about creating a multi-layered experience that’s not possible with fiction. With fiction, you do have to be careful to stay on task, as I like to call it, and make sure that every detail serves the story in some way. That sometimes means leaving out things you’d like to include. While I was reading Painting the Wild Frontier, I noticed that the information in your captions was not just repetition of material in the text but new information. I can’t think of any way a writer could add additional details to fiction without taking readers out of their experience of a fictional world.

Research

GG: Though I heard about Ethan Allen as a child, I didn’t discover him, so to speak, until I was in college doing research for a paper on New England folklore. I ended up doing another paper on his memoir. Then I sat on the material for many years before I did anything with it. Was Catlin someone you discovered recently or did you live with him for a long time before you started working with the material?

SR: When I started this project, I was vaguely familiar with Catlin’s paintings of North American Indians, as many people are. But I didn’t know anything about his life. I didn’t know about the "Indian Gallery," for example, or that he had traveled and painted throughout South America. The fact that he had written many books was also a wonderful surprise. I was excited that there was so much primary source material to work with.

SR: When I started this project, I was vaguely familiar with Catlin’s paintings of North American Indians, as many people are. But I didn’t know anything about his life. I didn’t know about the "Indian Gallery," for example, or that he had traveled and painted throughout South America. The fact that he had written many books was also a wonderful surprise. I was excited that there was so much primary source material to work with. GG: Among your many sources are four works by George Catlin in which he wrote about his travels. The editions were from the 1840s and 1860s. Have his works not been reprinted since then, or did you choose to go with early editions for some reason? Either way, did you have trouble getting hold of those old volumes?

SR: I used both modern and 19th-century editions. Some of Catlin’s books have been reprinted in modern editions, but not all. The modern editions are useful because of the commentaries and essays by editors, but in some cases, Catlin’s original text has been cut. I actually consulted four different editions of his most important book, Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Condition of the North American Indians. Also, I felt most comfortable quoting from early editions because they’re all in the public domain.

Luckily, I live near New York, and the New York Public Library owns the early editions. They don’t circulate, but you can sit in the main reading room and use them there. There’s something very magical about sitting in that spectacular room and holding in your hands an old, cracked, leather-bound book that no one has looked at for years.

Here’s a picture of the Rose Reading Room. You can see why I like to spend time there. It’s like a temple to scholarship.

Technology is evolving so fast that if I were researching this book today, I wouldn’t need to go to the library as often. Some of the early editions of Catlin’s books are available on Google Books.

GG: How was George as a writer?

SR: His first book, Letters and Notes, is his most famous. Most of it was originally published as a series of letters in a New York newspaper, and he later reworked the letters into a book. The letters describe his travels out West in the 1830’s, visiting and painting different tribes. The writing is colorful and dramatic, albeit a bit flowery and romantic in a 19th-century way. I get the feeling that he’s very conscious of his role as a storyteller, and that he’s trying to convey a sense of himself as a bold adventurer in an exotic land. He strives to be objective, but sometimes the tone is a little self-aggrandizing. At the same time, some of the material is very valuable as a record of Indian ways of life that have been lost. In a way, he was an anthropologist before there was such a thing as anthropology.

His later books are a bit over the top. He gets carried away with himself. That’s probably why they’re not read much anymore, except by scholars.

GG: Though I think I’ll probably try writing a true historical novel at some point, I’m actually afraid to write real history. My high school American history teacher gave us a talk on plagiarism that had me trembling in my seat, for one thing. For another, I’m anxious about making any kind of assessment without, essentially, justifying any thought I have with as much documentation as I can find. I’d be ibiding every half line. (Which is pretty much how I wrote my college papers.) I don’t see writers doing that. In fact, I’m reading a strange history/memoir right now that uses no citations at all.

How do you guys decide where to cite sources? I know you used them wherever you used a quotation, but, otherwise, where do they need to be used?

SR: Anything that’s a direct quote gets a citation. As for plagiarizing, that’s why it’s important to take careful notes. When I’m researching, I read at my desk and type my notes directly into the computer, making sure to write down the page number of every quote, and also making sure to phrase my notes in my own words so that I don’t accidentally end up using someone else’s words. After a book is written, I triple check the quotes and page numbers.

When I researched Painting the Wild Frontier, I gave every book I consulted its own section of notes. Then, when I was ready to write, I used the “Find” feature to assemble the notes for each chapter. To give you an idea of the scale of what I’m talking about, I took 263 single-spaced typed pages of research notes for this book. That doesn’t include the notes I had to keep about negotiating permissions and fees for the illustrations.

GG: Organizing my research after the fact was a big problem for me. Typing notes directly into the computer so you can search for material later sounds like a great idea.

SR: It’s hard to imagine tackling a project like this without the computer. It would’ve taken ten years!

The Past

GG: In addition to your historical novel and Painting the Wild Frontier, you’ve written a biography of Clara Schumann, a nineteenth-century figure, and a picture book biography of Jose Limon, a twentieth-century dancer. Why the big interest in the past? (And I ask that as a history fan, myself.)

SR: I don’t really think of my books as taking place in the past. I think of them as stories of interesting people who inhabited times and places that are different from ours. Their feelings and motivations are human, and that’s why we can relate to them.

GG: So would it be accurate to say you think of the time these people inhabited as the setting for your work, the way a fiction writer might think of setting? You just have to do a great deal of work on your settings?

SR: It’s like that old phrase, "the past is a foreign country." If I were writing a novel that was set in a foreign country, I would try to spend as much time there as I could, in order to learn about the culture. I’d want to know about the customs, religion, language, politics, social relationships, ways of working, childrearing practices, artistic expressions, etc. Since I can’t actually visit the past, I use research, particularly primary sources, to experience it. I guess I’m an anthropologist in my own way.

GG: Why write about these people in books for children instead of adults?

SR: I enjoy the challenge of taking complex material and finding a way to make it comprehensible to children, without dumbing it down. Part of the process is about finding the essence of the story and letting go of the details that are less relevant. I hope that my books will help kids understand themselves and the world we live in.

A book can have a big impact on a child. There are books I read as a child that changed my life. That doesn’t happen with adults too often.

GG: While I appreciate the beauty of George Catlin’s work and believe it’s significant because artists (particularly in the days before photography) provide documentary history for us, I find it difficult to actually like him, in large part because in my mind he neglected his family. Yet I know all kinds of unpleasant things about Ethan Allen, and I still like him. Mainly, I think, because I knew men like Allen while I was growing up, and I think I understand why they were the way they were. Do you like George Catlin? And, of course, why or why not?

SR: Catlin had his strengths and his weaknesses, as we all do. It’s easy to be disapproving of the way he sometimes put himself and his work ahead of his family. But I think it’s important not to judge him by today’s standards. Men at that time were not expected to directly participate in childrearing. What may seem like selfish behavior to us wasn’t necessarily seen that way by Catlin and his contemporaries. I talk about this in the book.

When I was writing his biography, I really didn’t think about whether I liked Catlin or not. I just tried to tell what happened and to let readers come to their own conclusion about whether he was likable or admirable.

My feelings about him are complicated. I admire his courage and boldness, his sense of adventure, his artistry, and his dedication to his work. I also think he was sometimes foolhardy and deluded. What’s undeniable is that he led a fascinating life, and that his paintings and writings are historically and artistically significant.

GG: And, finally, I’ve read for years that Americans don’t know much about history, that it’s given little attention in schools. How would you like to see Painting the Wild Frontier used with child readers?

SR: I’d like to see the book used as a jumping-off point. It touches on so many different aspects of American history and world history. It’s not just the story of one man’s life. It’s about artists and the role they play in society; about American Indians and the settlement of the West; about scientific exploration. Any chapter of the book could serve as a point of departure for further research into the Pipestone Quarry, the indigenous peoples of the Amazon, 19th-century portrait painting, or the history of lacrosse. The possibilities are endless. I’d also like the book to prompt conversations about American Indians, stereotypes, and the interaction of cultures.

The Painting the Wild Frontier: The Art and Adventures of George Catlin blog tour continues tomorrow at OneBookTwoBook.

Image Credits: Susanna Reich--Laurel Golio

Stu-mick-o-súcks, Buffalo Bull's Back Fat, by George Catlin-- Smithsonian American Art Museum

2 comments:

Susanna and Gail,

What a fantastic interview. I love the temple to scholarship, and laughed at the thought of ibiding (and this generation has it so much easier. I know at Umass, and expect most other university libraries, there's a program called Refworks; once you find your reference online, you click it, and it will set up your citations for you in MLA style or any other you choose.)

I love the idea of history as setting. This afternoon I'm talking about children's nonfiction to a class Jo Knowles is teaching at the Eric Carle museum, and I'll tell them they must read this.

thanks! Jeannine Atkins

Wow, Jeannine. Thanks so much.

Post a Comment